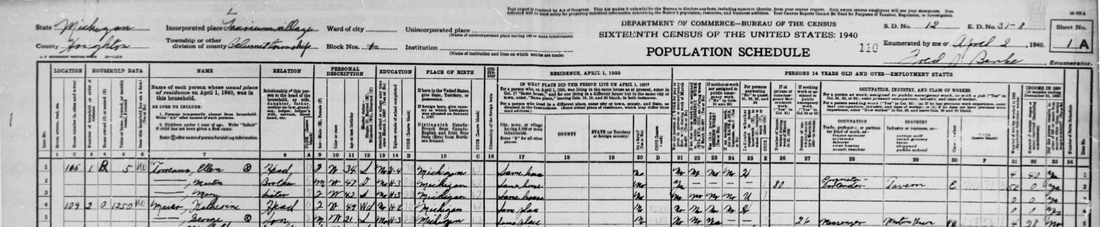

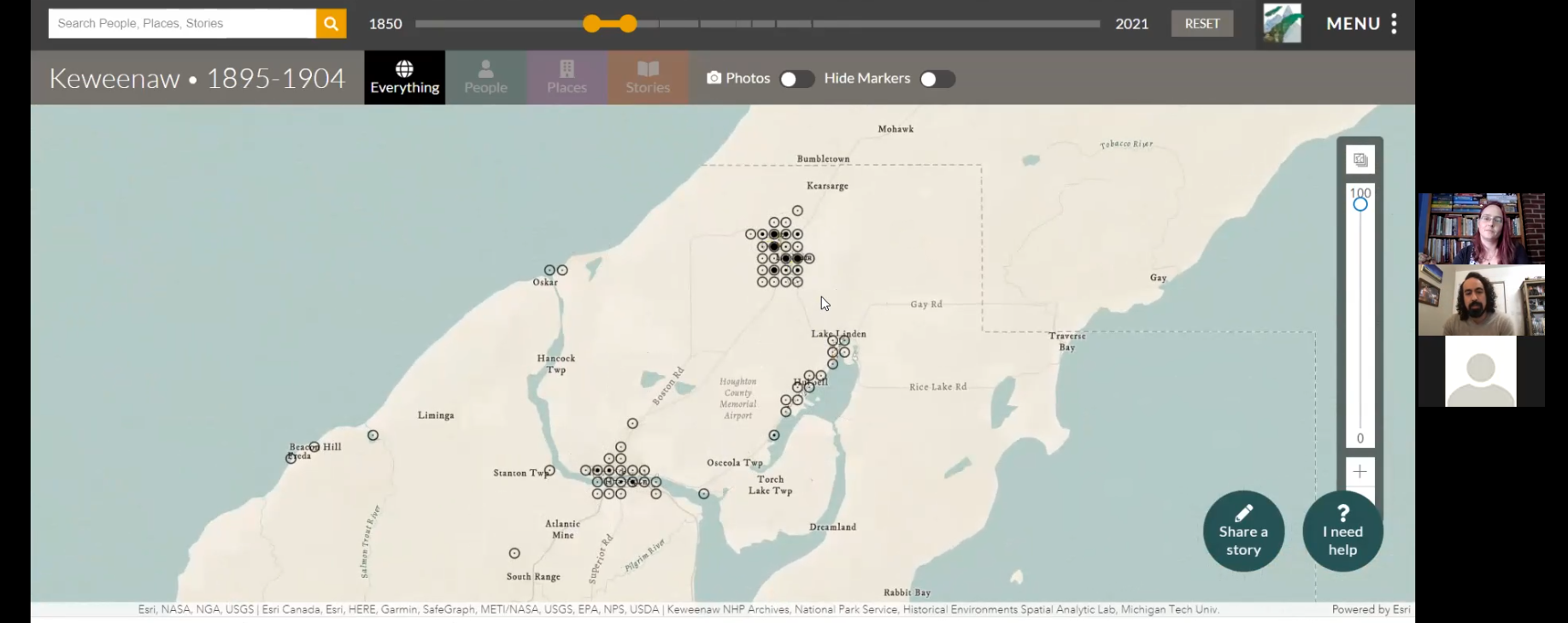

Geocoding the Census: Reuniting Historical People and Communities in the Keweenaw Time Traveler4/26/2022 Author: Dan Trepal In a previous blog post, we discussed the US decennial census, which is a key part of the upcoming version of our Keweenaw Time Traveler web interface. This huge, detailed record set gives us an intimate view of the lives of almost 380,000 historical residents of the Copper Country. But how did we transform this huge set of census records into an interactive digital atlas? A crucial step in that transformation is the process of geocoding. In today’s blog post I will give a quick overview of the process of geocoding and how we used geographic information systems (GIS) software - plus a lot of elbow grease – to populate the Time Traveler’s digital representation of the historical landscape with the people who lived and worked there. What is Geocoding? As I explained in my blog post on the census, census records can now be obtained in a digital database format that is ‘machine readable’, or in other words easily stored and manipulated on a computer. Geocoding is the process of taking each record in the census (or any piece of digital information) and assigning real-world spatial coordinates to it – a spot on the earth. This spot could be any kind of ‘place’ - a country, a state, a county, a town, a street, a home address – even a tree or other specific landmark. Anything with a known location can serve as the ‘target’ for geocoding and have digital information attached to it. Geocoding historical data like the census can be a challenging task, for several reasons. One important problem we face is common to all historical research: historical records are usually incomplete and contain uncertainties and inaccuracies. Beginning in 1880 the census was collected by an army of enumerators – temporary employees from each community who were given basic instructions before going door-to-door filling out the census form for hundreds of households, which were later gathered together to form the census record. Overall, these enumerators did a very good job, but in many cases addresses are vague or missing, names are misspelled (how often would you spell another person’s last name correctly after hearing it just once?), or the handwriting is illegible, among other things. On top of all that, the digital version of the census we are working with was transcribed from microfilm photos of those original copies by volunteers with no local knowledge – how easy is it to read a digital scan of a microfilm copy of a smudged cursive handwritten rendering of ‘Amygdaloid Street’? A local to the Keweenaw might recognize this geological term, because it is part of our mining heritage, but others might never guess it! Cleaning Up Historical Data The first step in geocoding the census, then, is to ‘clean up’ the digital data, focusing on correcting errors or gaps in place names – street numbers, street names, or references to mining locations or even buildings in some cases. We do this manually, going through each record and correcting the address information to a standard set of terms. This is long, hard work. But we have learned, though extensive experience, that computers still struggle to interpret this sort of information automatically. The path between a person living in Houghton in 1880 – for example - and our current record of their existence relies on a sort of 140- year game of telephone, with information being recorded, stored, copied, and converted into different forms and for different purposes over time. During this process information can be lost, altered, or simply garbled. Once we have cleaned up the data so that everyone’s address information is as legible as we can make it, we can move on to the actual process of geocoding. Geocoding requires two pieces of information – the location of the record you want to map, as described in the record itself, and the place in the real world where you want to map the record to. In the Keweenaw Time traveler, that second piece of information exists as a series of points on our digital map of the historical landscape. Building a Historical Digital Landscape for the Census Records Here is where we run into another challenge – more gaps in the historical record. The only way we can put a point down on our digital map to represent a historical home is to have a historical record of that place’s location - usually a historical map that shows where that home was and lists the address of the home. Luckily, we have historical Sanborn fire insurance maps that provide both of those pieces of information. But even these present us with a problem. They only cover part of our landscape, and only for certain years. So how do we map people if we can’t find their house on a historical map? Alternately, what if their census record is missing key address information, like the house number or street name? To deal with this challenge, we have created four levels or scales of digital historical geography that serve as destinations for our census records on our digital historical map of the Keweenaw: Buildings, Streets, Settlements, and Enumeration Districts. Building these digital places is the next major step in the geocoding process. Buildings: Where our historical maps show the locations and addresses of buildings, we can create a digital copy of them in our GIS software that contains the building’s real-world coordinates. This is the ‘gold standard’ for our geocoding work, the most accurate scale we can capture when the historical address data in the census is complete and the address falls within our Sanborn map coverage area. Streets: We also created a map of the centroid of historical streets (the middle point along the street’s length) in the KeTT. Records with incomplete addresses, but with an identifiable street name, can be mapped to this point. This represents an approximate location where we are reasonably certain which street a person lived on, but unsure exactly where on the street they lived. Settlements: This scale of geographies represents ‘places’ in the Keweenaw – this could be a village, or a mining location, or a fishing camp, or any other small place, usually in the rural parts of the Keweenaw, where street addresses are vague, don’t exists, or only existed for a short time. We can also create a Settlement point for larger towns, so that if the census record is clear that a person lived in, say, Calumet, but their home and street address information is missing or illegible, we can still map them to the town they lived in. Enumeration Districts: The Census Bureau has created special districts for collecting the census, called Enumeration Districts. This is a way to divide up the landscape into specific ‘districts.’ Each census enumerator is responsible for collecting records on all the people within their district. Every census record is labeled with the district it was collected within. This means that 100% of the census is mappable to enumeration district. Even if the home address, street name, and any other location information is missing or garbled, we can still map people to the enumeration district – in our case to the centroid of the district boundary (the middle point, as with the streets). But in order to do that we had to reconstruct the district boundaries from old maps and descriptions – these records were often sketchy or incomplete, making their reconstruction a difficult process. But the Enumeration Districts serve as an important ‘catch-all’ geography, so the effort is very much worth it. Time to (Finally) Map it! Now that we have cleaned up our census records, and created a digital historical map of the geographical destinations for all our people, the hardest work is done (whew!). Next comes the key step of actually doing the geocoding. We start by building address locators – these are a kind of digital geographic key that tells the computer where to put records based on their cleaned up location information. We convert our four scales of geographical destinations into a digital table that the computer can compare to the addresses in our census records. When the computer found a match between a census record and one of our destinations, it maps that record to that place. Voila! - this process of comparing and matching is the actual geocoding step. The product of that process is a new digital file in the GIS software where each person is represented as a point in space, with all their census information attached in a database. Depending on how compete their address information was, each person is mapped once, to the most detailed geography we can match them to – Buildings if possible, then Streets, then Settlements, and finally Enumeration Districts if there is not enough information to map them to any of the previous three scales. So how did it go? You’ll soon find out! When the newest version of the Keweenaw Time Traveler launches this summer, you will be able to search and explore this new database of mapped historical Copper Country residents using our upgraded, map-based interface. As you can see, a lot of hard work and historical sleuthing happens behind the scenes in order to turn an enormous, but valuable, historical record into something that is fun and easy to explore. It also gives us a chance to see historical people within a visual picture of their historical landscape. Seeing people mapped this way allows us to start seeing things like streetscapes, neighborhoods, and the pathways of daily life. In doing this, we are re-using the census for a purpose that its original enumerators and tabulators never dreamed of - detailed peek back into the past that can now be preserved and explored by future generations.

0 Comments

Our weekly Lunch Time Chat is out!! This week James Juip sits down with Dr. Dan Trepal to discuss the US decennial census and how it is used in the new Keweenaw Time Traveler Explore App! Author: Dr. Dan Trepal The Keweenaw Time Traveler Project is designed for exploring the historical people, places, and stories of the Keweenaw and Copper Country. Our information about historical people comes from a wide variety of historical records, and the largest and most detailed set of records we have to work with is the US decennial census. Our latest version of the Keweenaw Time Traveler App will launch this summer with a huge new amount of historical data drawn from the census. Let’s take a minute for a quick overview of what the US census is and what you will be able to learn from census data in the Keweenaw Time traveler. The US Constitution contains provisions for conducting a ‘decennial’ (once every ten years) census, which is a detailed count of the nation’s population. The US government conducted its first census in 1790, and has continued to do so every ten years, through the latest census in 2020. Since 1902 the census has been managed by the US Census Bureau. For people interested in history the census is a priceless record. This is because it attempts to record each and every US citizen, and includes important details including their name, address, age, sex, family status and composition, occupation, immigration status, country of origin, language spoken, and literacy, among others. As a result, the census is the largest, most detailed, and most complete record we have for people living in the US - and in the Copper Country! - and it preserves many fascinating details about their lives. All US Census records have been retained by the Federal government - and while they are public records, the sheer size of the censuses (in their original paper form, or as microfilm copies) makes them difficult to use for historical or genealogy research. These physical records are also at risk of damage, like any archival document. In 1921, a portion of the records for the 1890 census were damaged in a fire in a federal repository in Washington DC, and most of the damaged records were later destroyed. As a result, the 1890 census has largely been lost. This led to more careful storage, but highlighted the need for a better way to store and access the census. Beginning in the 1990s, a large research project called the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series, or IPUMS, began creating a digital version of the US census records. This eventually grew into a collaboration with the genealogical organization FamilySearch and the genealogical companies HeritageQuest and Ancestry.com. IPUMS has also built their own online portal for accessing census data. The result of this huge ongoing project is that census records now exist in a searchable, digital online format that is much more accessible to experts and the public alike. IPUMS has also expanded its census work to other national censuses, so that it now includes a total of about 1 billion individual records from more than 100 countries. The Keweenaw Time Traveler project has partnered with IPUMS to incorporate census data for the Houghton and Keweenaw counties for the period from 1880 through 1940 (excluding the ‘lost’ 1890 census). Our census dataset contains nearly 380,000 individual records for this period, making it the biggest record set in the Keweenaw Time Traveler. The census data helps us to ‘populate’ the historical Copper Country with the people who lived and worked there in the 19th and 20th centuries, with all the details showing their backgrounds, livelihoods, social connections - in short, hundreds of thousands of the individual life stories that make up the heritage of Copper Country. In a future blog post, we will talk more about how we have mapped people in these censuses to our digital historical landscape in the Keweenaw Time Traveler, tying the original census data even more closely to the historical landscape of the copper country, and making it easier for you to explore your history.

In anticipation of the upcoming launch of our new Explore App the KeTT team is hosting a new video series! Every Thursday host James Juip will sit down with fellow KeTT team members for a lunch time chat, discussing all the great work our team is doing to develop some exciting new things that will be a part of our new release. This week James sits down with Dr. Sarah Fayen Scarlett to discuss the new Keweenaw Time Traveler Explore App and recent design charrettes put on by the Time Traveler Team. Author - Dr. Sarah Fayen-Scarlett Building the Keweenaw Time Traveler has always been a group effort. It takes many different people to ensure this resource will be an engaging public history project, a powerful tool for research, and also accessible to as many users as possible. One way that our production team seeks input from future users is through “Design Charrettes.” In urban planning, a design charrette brings together stakeholders to collaboratively develop a solution to a shared design problem. The Keweenaw Time Traveler team has been holding design charrettes since our early years to make sure that users with different kinds of experience will be able to access and enjoy it. This Spring, as our production team is finalizing the new design and user interface, we have been holding Design Charrettes to guide the development of Help resources. What do users need to know to make the most of the Time Traveler’s resources? Which parts of the interface are less intuitive than others? What should our Help buttons provide? We held two different charrettes — one to test the data search functions and another to test the map interfaces. We held these charrettes on Zoom to keep everyone comfortable amid changing COVID restrictions, but also because earlier Zoom charrettes in 2020 had alerted us to the advantages of watching people interact with the Time Traveler on their own home computers. We invited users from the immediate community and partners from regional heritage organizations to join us for an hour of online exploration and follow up discussion. After a brief introduction, each participant went into a “breakout room” with two Time Traveler team members. The participants shared their screen and the team member asked them to use the Time Traveler in specific ways – Can you find the home of a certain person? How far did their children have to walk to school in Calumet in 1921? Is it clear how to switch the base maps? Participants always had a chance to explore freely so they could show us how they wanted to use the Time Traveler and how the user interface could be tweaked to improve their experiences. The whole group always came back together to debrief and share observations from the break out rooms. Afterwards, the Keweenaw Time Traveler production team develop a list of changes in direct response to participant feedback. We appreciate all the time our participants gave these charrettes. Thank you! Participants included local residents who use the Time Traveler a lot, Michigan Tech students and researchers, and staff of Michigan Tech University Archives and Historical Collections and the Keweenaw National Historical Park.

In anticipation of the upcoming launch of our new Explore App the KeTT team is hosting a new video series! Every Thursday host James Juip will sit down with fellow KeTT team members for a lunch time chat, discussing all the great work our team is doing to develop some exciting new things that will be a part of our new release. This week James sits down with Ryan Williams and Matt Monte of Monte Consulting to discuss their partnership in developing the new Keweenaw Time Traveler Explore App. Please tune in next week when James and Dr. Sarah F. Scarlett discuss design charettes and their role in the app development process.

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed